Holidays, that is. As you know from my last post, I decided to sew some Christmas presents. Some decision-making and present-sewing was still happening at the very last minute, i.e. the evening before we bundled ourselves, our luggage and provisions and our wrapped presents into the car for the long drive to the GTA.*

What you won't likely have picked up from my last post is that all the sewn gifts this year were repurposed and/or sewn from stash. I'm not exactly sure how this happened, but it did. Yay for stashes!

Of particular interest, the furry thing gracing my dress form is a fur blanket made from a great-quality fake fur coat which (luckily) was XL and quite long so it made a decent-sized rectangular piece. It's lined with 100 weight fleece from stash. I had a brainwave that my 20 yo son would love such a thing, and he does. That's good, because it was a pain to make. First, there are all the dust animals (bigger than bunnies) which are produced when you cut the fur. Then, seaming the fur pieces so the seams were invisible, more or less, took a few tries since any unevenness is instantly visible as a texture change. I did this by hand, from the back. Last but not least, sewing on the fleece backing was a challenge since the fleece would not stay still on the fur - I swear I did not have to touch it for it to start creeping along the nap of the fur. I laid the fur piece on the floor, fur side up (creating more animals), positioned the fleece on top so it was more-or-less even, pinned extensively, picked up the whole mess, and sewed one side. I started with the top edge, i.e. with the fur nap running away from it. Rinse and repeat, as they say, saving the bottom edge to last.

The boy says now that I've figured out sewing with fake fur, could I puhleeze make him a new zip-in lining for his leather Engineering jacket in something a little wild. He'd have to come fabric shopping with me so it may not happen.

Next up? I'm buoyed up by the success of the eyeglasses cases I made from leather to get back (finally) to my leather jacket. Had you forgotten about it? Well, I haven't. Poor one-sleeved thing, it has been languishing in the sewing room in plain view for almost two whole months, and it is ABOUT TIME I finished it. But it's stuck in the sewing queue behind a couple of active-wear items that I cut out in a burst of enthusiasm and leather-jacket-denial before the OMG-Christmas-is-coming moment. I want to get these projects off the cutting table and into a drawer before I do the jacket, since I've got to free up the cutting table for the jacket lining (see, it does make sense). I can't do all this before 2011, since I foolishly signed on to work the rest of this week, but I intend to at least make a good start by the end of next weekend.

After that I want to muslin Vogue 1083 and get serious about sewing a new outside for my inside-out fur coat.

No other retrospectives on 2010, predictions for 2011, or optimistic resolutions from the Sewing Lawyer will be served. I'm eager to see how it all rolls out. Stay tuned!

* For those of you who don't know the term, the GTA is the Greater Toronto Area, also known as "the 905" (for its area code, to distinguish it from the 416 which is Toronto proper). I know that the GTA looks like a small town in comparison to many cities of the world (it's only the 45th biggest metropolitan area in the world, with 5.6 million people). However, getting there and getting through it are a chore.

Tuesday, December 28, 2010

Sunday, December 19, 2010

Santa's workshop

I was hit by a sudden panic two weeks ago. So I've been busy. However, I'm now less stressed.

About the little pile of zipped leather containers pictured above - some time ago one of my local sewing friends gave out a pattern for an ingenious case for eyeglasses. Hers was made from fabric but I chose to use leather, most of which came from thrift store leather skirts.

The piece is 21.5" long by 2 5/8" (52 x 6.5 cm) wide, with round ends. Interface the piece with fusible. Find a zipper of about 24" (60 cm) in length.

Sew the zipper to the leather, starting with the bottom end of the zipper at a point about 2.5" (6cm) from one end and continuing to a similar point at the other end. Then repeat, going in the opposite direction. You may have to rip and re-establish the stopping point to ensure that it zips up evenly (you will immediately see what I mean if you make one and it doesn't). The further away from the end you start, the fatter and shorter the resulting case will be. I thought 2.5" produced a case with a good length to width ratio.

When sewing the zipper around the round end, you will need to clip into the zipper tape to let it curve.

Then topstitch from the right side.

Next, you have to trim the open ends of your zipper and secure them inside with a couple of hand stitches.

To line, cut the same piece from thin (100 weight) polar fleece or similar fabric. Remove about .25" (7mm) from the edges.

Coat the wrong side of the leather piece with rubber cement. Let it dry a bit, then place your fleece piece on top, patting it down so it sticks to the glue.

Attach the lining to the zipper tape with hand stitches.

Start to zip ...

And you're done!

About the little pile of zipped leather containers pictured above - some time ago one of my local sewing friends gave out a pattern for an ingenious case for eyeglasses. Hers was made from fabric but I chose to use leather, most of which came from thrift store leather skirts.

The piece is 21.5" long by 2 5/8" (52 x 6.5 cm) wide, with round ends. Interface the piece with fusible. Find a zipper of about 24" (60 cm) in length.

Sew the zipper to the leather, starting with the bottom end of the zipper at a point about 2.5" (6cm) from one end and continuing to a similar point at the other end. Then repeat, going in the opposite direction. You may have to rip and re-establish the stopping point to ensure that it zips up evenly (you will immediately see what I mean if you make one and it doesn't). The further away from the end you start, the fatter and shorter the resulting case will be. I thought 2.5" produced a case with a good length to width ratio.

When sewing the zipper around the round end, you will need to clip into the zipper tape to let it curve.

Then topstitch from the right side.

Next, you have to trim the open ends of your zipper and secure them inside with a couple of hand stitches.

To line, cut the same piece from thin (100 weight) polar fleece or similar fabric. Remove about .25" (7mm) from the edges.

Coat the wrong side of the leather piece with rubber cement. Let it dry a bit, then place your fleece piece on top, patting it down so it sticks to the glue.

Attach the lining to the zipper tape with hand stitches.

Start to zip ...

And you're done!

Sunday, December 5, 2010

Not the usual Sewing Lawyer style

I'm a member of a group of local sewers (sewists, if you prefer). We got together initially because we all owned PatternMaster Boutique (PMB) a pattern-drafting computer program. We still do, and we even use it - but it turns out we're also somewhat omnivorous when it comes to patterns and all of us are on the lookout for good ideas most of the time. So when one of our membership showed us a simple drapey jacket that she had made, and when we all - different ages, sizes and builds - tried it on and looked pretty good in it, we were intrigued. We decided we should all purchase suitable fabric and, with our sergers, make our own.

Here's mine.

This jacket design was attributed by my friend to Carter Smith, an American fibre artist who specializes in shibori dying. There's more about him here.

Shibori is a "Japanese term for several methods of dyeing cloth with a pattern by binding, stitching, folding, twisting, compressing it, or capping. Some of these methods are known in the West as tie-dye", to quote Wikipedia.

The jacket design takes advantage of the type of fabric Carter Smith tends to work with - drapey silk with beautiful pattern or surface design. This is because it's made with only two (2) pieces, and each of them is just a big square.

The jacket design takes advantage of the type of fabric Carter Smith tends to work with - drapey silk with beautiful pattern or surface design. This is because it's made with only two (2) pieces, and each of them is just a big square.

After I was introduced to the idea of this jacket, the perfect fabric presented itself. This was from Fabricland of all places - it's 85% silk and 15% metallic. It has a lovely soft hand and is supremely drapey - the crinkles don't lessen much and if they do, a quick dunk in the sink brings them back with no ill effects, I discovered. Great stuff! I bought the last of the bolt and it was the perfect amount for these two pieces.

The second piece is this top, which is essentially a tube (CB seam) with shoulder seams and simple slit arm openings.

So, do you want to know how to make the jacket?

First, you need 2 squares of your chosen fabric. The small one's sides are half the length of the sides on the big square. My sample squares measure 12" and 6".

Instructions for a bias garment like this jacket were published in issue no. 143 of Threads Magazine ("Get biased - create a bias topper from two squares of fabric"). However there is a serious error in the article as published. It said to adjust the size of the smaller square according to your hip measurement - and that the diagonal measurement on the small square should be 1/2 your hip measurement. In the next issue, after several people complained that this made a garment which was much too small, Threads acknowledged that each side of the small square should be 1/2 your hip measurement. (Or, more straightforwardly, each side of the large square should be the same measurement as your hip circumference...) My jacket squares are 40" and 20".

Place your small square on the big one, right sides together, with edges matching at one corner. Sew the edges together using a narrow seam. If you trust your fabric you can use a rolled hem on the serger to do this. I used a 4 thread stitch on my serger but without the stitch finger - the resulting seam is rolled, a bit wider than the rolled hem, but much stronger.

(If you click on the pictures, they should enlarge.)

The next step is to take the free corner of your small square, and pull it diagonally across so the edges match those of the opposite corner of the big square. Then, mark a point some distance away from the pointy ends of the resulting triangle. For a full-size jacket, 10" is about right; at right my opening is about 3", and is marked with pins.

Sew the right angle of the triangle from one marked point to the other, i.e. leaving the pointy ends unsewn.

Take that pointy end and fold it down so the free corner is above the end of your stitching, and the unsewn edges are matching. Sew the remaining open sides of that little square.

At this point you have a fully enclosed thing which is vaguely triangular with a square bottom. To turn it into a wearable garment you have to cut openings at the bottom, sleeve ends, and neck. A front opening is optional since you can make this as a pullover.

For the bottom (hip) opening, you slit the small square diagonally. In the photo at right, I've marked where the ends of the slit will be with little stickers. It seems slightly counterintuitive to cut in this direction, but just do it - if you paid attention to your intuition at this point, there would be tears...

Do the same thing at the pointy ends of the triangle, which by now you may have guessed will be the sleeve openings.

This is a different sleeve finishing method than in the Threads article - they want you to just cut the pointy end off. This method makes a neat little gusset instead - it fits better and I think looks better than a batwing shape ending right in the cuff.

Then find the neck point by folding your jacket in half. Mark this point with a pin.

If you are making a jacket, cut open the CF up to the point marked by the pin at neck point.

Here's what the jacket looks like, in basic outline. Try it on now to check that the neckline works. You may need to cut it further into the back, and you may need to widen the opening.

Obviously, for a real garment you would, once satisfied, finish all the edges using a narrow rolled hem.

But my client insisted on trying her jacket on, right away!

Here's mine.

This jacket design was attributed by my friend to Carter Smith, an American fibre artist who specializes in shibori dying. There's more about him here.

Shibori is a "Japanese term for several methods of dyeing cloth with a pattern by binding, stitching, folding, twisting, compressing it, or capping. Some of these methods are known in the West as tie-dye", to quote Wikipedia.

After I was introduced to the idea of this jacket, the perfect fabric presented itself. This was from Fabricland of all places - it's 85% silk and 15% metallic. It has a lovely soft hand and is supremely drapey - the crinkles don't lessen much and if they do, a quick dunk in the sink brings them back with no ill effects, I discovered. Great stuff! I bought the last of the bolt and it was the perfect amount for these two pieces.

The second piece is this top, which is essentially a tube (CB seam) with shoulder seams and simple slit arm openings.

So, do you want to know how to make the jacket?

First, you need 2 squares of your chosen fabric. The small one's sides are half the length of the sides on the big square. My sample squares measure 12" and 6".

Instructions for a bias garment like this jacket were published in issue no. 143 of Threads Magazine ("Get biased - create a bias topper from two squares of fabric"). However there is a serious error in the article as published. It said to adjust the size of the smaller square according to your hip measurement - and that the diagonal measurement on the small square should be 1/2 your hip measurement. In the next issue, after several people complained that this made a garment which was much too small, Threads acknowledged that each side of the small square should be 1/2 your hip measurement. (Or, more straightforwardly, each side of the large square should be the same measurement as your hip circumference...) My jacket squares are 40" and 20".

Place your small square on the big one, right sides together, with edges matching at one corner. Sew the edges together using a narrow seam. If you trust your fabric you can use a rolled hem on the serger to do this. I used a 4 thread stitch on my serger but without the stitch finger - the resulting seam is rolled, a bit wider than the rolled hem, but much stronger.

(If you click on the pictures, they should enlarge.)

The next step is to take the free corner of your small square, and pull it diagonally across so the edges match those of the opposite corner of the big square. Then, mark a point some distance away from the pointy ends of the resulting triangle. For a full-size jacket, 10" is about right; at right my opening is about 3", and is marked with pins.

Sew the right angle of the triangle from one marked point to the other, i.e. leaving the pointy ends unsewn.

Take that pointy end and fold it down so the free corner is above the end of your stitching, and the unsewn edges are matching. Sew the remaining open sides of that little square.

At this point you have a fully enclosed thing which is vaguely triangular with a square bottom. To turn it into a wearable garment you have to cut openings at the bottom, sleeve ends, and neck. A front opening is optional since you can make this as a pullover.

For the bottom (hip) opening, you slit the small square diagonally. In the photo at right, I've marked where the ends of the slit will be with little stickers. It seems slightly counterintuitive to cut in this direction, but just do it - if you paid attention to your intuition at this point, there would be tears...

Do the same thing at the pointy ends of the triangle, which by now you may have guessed will be the sleeve openings.

This is a different sleeve finishing method than in the Threads article - they want you to just cut the pointy end off. This method makes a neat little gusset instead - it fits better and I think looks better than a batwing shape ending right in the cuff.

Then find the neck point by folding your jacket in half. Mark this point with a pin.

If you are making a jacket, cut open the CF up to the point marked by the pin at neck point.

Here's what the jacket looks like, in basic outline. Try it on now to check that the neckline works. You may need to cut it further into the back, and you may need to widen the opening.

Obviously, for a real garment you would, once satisfied, finish all the edges using a narrow rolled hem.

But my client insisted on trying her jacket on, right away!

Sunday, November 28, 2010

The Blue Gardenia

I'm in SUCH good company over at the Blue Gardenia. Denise is doing a series on sewing spaces. She has already given us access to the sewing spaces of your favorite bloggers, and today, she's featuring my (rather messy and despite what she says, disorganized) sewing room. Head on over there to have a peek at the chaos in which The Sewing Lawyer turns out her projects.

For fun, here's another picture:

For fun, here's another picture:

Saturday, November 20, 2010

A new trick - Spanish snap buttonholes

It's good to stretch your skills by trying something new, right? The Sewing Lawyer challenged herself by trying the "Spanish snap" buttonhole technique today. The instructions can be found in Roberta Carr's book Couture: the art of fine sewing. Or, read on...

First, here's what a Spanish snap buttonhole looks like (click on the photos for eye-popping close-up detail).

This technique came to mind for the project of re-lining my Auckie Sanft jacket. One of this jacket's fantastic features is that it's lined to the front edge. But... that meant that its buttonholes were originally sewn through both the fabulous Linton tweed, and the lining fabric behind it. Removing the lining meant literally cutting the lining fabric out of the buttonhole stitches. I needed a way to make buttonholes that would lie behind the original ones and look good from the inside. The latter requirement meant that sewn buttonholes were instantly rejected. (Sew buttonholes in one layer of lining fabric? No thank you!)

Then I remembered reading that Chanel jackets sometimes had bound buttonholes made in the lining to back sewn buttonholes in the outer jacket. And I dimly remembered the Carr technique.

What's not to like? Here's how to make them.

First, mark your buttonhole placement on the fashion fabric. Then cut little patches that are big enough so that ON THE BIAS (this is important!) they are as long as your marked buttonholes, plus about 2.5cm (1") on either end. Mark the patch (wrong side) with a line that represents the centre line of your buttonhole, and the ends of the buttonhole. Then draw (lightly) a pointy oval shape (like a flattened football) that is about 6mm (1/4") wide at its widest, centred on the marked line. Carefully pin your patch to the markings for your buttonholes, right sides together.

Sew around the marked football, pivoting at the pointy ends, using teeny-tiny stitches (1mm on my machine). Here's a close up of the stitched patch. You can see I've trimmed my patch to an oval shape. Ms. Carr suggests starting with this shape but it really doesn't matter.

Sew around the marked football, pivoting at the pointy ends, using teeny-tiny stitches (1mm on my machine). Here's a close up of the stitched patch. You can see I've trimmed my patch to an oval shape. Ms. Carr suggests starting with this shape but it really doesn't matter.

First, here's what a Spanish snap buttonhole looks like (click on the photos for eye-popping close-up detail).

This technique came to mind for the project of re-lining my Auckie Sanft jacket. One of this jacket's fantastic features is that it's lined to the front edge. But... that meant that its buttonholes were originally sewn through both the fabulous Linton tweed, and the lining fabric behind it. Removing the lining meant literally cutting the lining fabric out of the buttonhole stitches. I needed a way to make buttonholes that would lie behind the original ones and look good from the inside. The latter requirement meant that sewn buttonholes were instantly rejected. (Sew buttonholes in one layer of lining fabric? No thank you!)

Then I remembered reading that Chanel jackets sometimes had bound buttonholes made in the lining to back sewn buttonholes in the outer jacket. And I dimly remembered the Carr technique.

Ms. Carr wrote: "Frequently used by the designers, this buttonhole has very thin lips that can hardly be seen. I like to call them 'invisible' bound buttonholes. The advantage of a Spanish snap buttonhole is that it can be made very small - as one might use on a silk blouse. On the other hand, Spanish snap buttonholes are equally effective used on a tweed or nubby fabric with the lips made from wool flannel or worsted."

First, mark your buttonhole placement on the fashion fabric. Then cut little patches that are big enough so that ON THE BIAS (this is important!) they are as long as your marked buttonholes, plus about 2.5cm (1") on either end. Mark the patch (wrong side) with a line that represents the centre line of your buttonhole, and the ends of the buttonhole. Then draw (lightly) a pointy oval shape (like a flattened football) that is about 6mm (1/4") wide at its widest, centred on the marked line. Carefully pin your patch to the markings for your buttonholes, right sides together.

Snip carefully along the marked centre line to (but not through) the stitches at the pointy tip. Then pull your patch through to the wrong side.

Next comes the magic, ineptly illustrated here because I was holding my camera with one hand. To quote Ms. Carr: "Holding each end of the egg shaped patch with the thumb and forefinger, pull in a snapping motion. One good 'snap' and the bias will wrap around the 1/8" (.3cm) seam allowances and automatically create tiny narrow lips."

This is the right side, even before pressing!

Magic, I tell ya!

No additional sewing is required - Ms. Carr says you can use a tiny bit of fusible web at each end to keep the patch in place. (I will however tack the patches to my jacket to keep the buttonholes in place.)

In other news, I had approximately 50 minutes while in Toronto to shop, and I wanted to do two things: visit Perfect Leather at 555 King Street West; and look for waterproof (or water-resistant) fabric for the fur coat.

Guess which one prevailed? (This photo from Perfect Leather's website.) All I can say is WOW! I think you can find any kind of leather; any colour; any finish; any size; any combination. Needless to say there is a very intoxicating and leathery perfume in the place. I bought 4 sq.ft. of orange goat leather for a little project...

Sunday, November 14, 2010

The edges of sewing

By which The Sewing Lawyer means an activity that has something to do with sewing but doesn't involve the actual activity of putting cut pieces of fabric together with thread. It includes choosing fabric (in a store or from the stash) and patterns, thinking about sewing, reading about sewing, and tracing patterns. More constructively, it may involve shoveling out the sewing room. This is a (rarely-seen) variation of sewing around the edges because it tends to result in recently-acquired fabric being handled, thought about, and put away, and leads to unfinished projects being unearthed, thought about, and sometimes even advanced (without actual sewing).

Because I feel I have truly started to "sew" until the machine has been turned on and a bobbin wound, I also include cutting out projects in this category, if I'm pretty sure I'm not going to turn the machine on and wind a bobbin imminently after cutting out the last piece.

Right now, I am marking time while waiting for my teflon foot to arrive so I can get back to the leather jacket. It's going to be a bit of a pain to translate the very precise settings I had been using (on Kathryn Brenne's Bernina) to the very imprecise settings available on the Featherweight, but I am determined.

So in recent days, quite a lot of stuff around the edges of sewing happened here. This included:

Today I feel like more, maybe to include tracing Jalie 3024, which I think I'll shorten for now to another top suitable for exercise wear.

Because I feel I have truly started to "sew" until the machine has been turned on and a bobbin wound, I also include cutting out projects in this category, if I'm pretty sure I'm not going to turn the machine on and wind a bobbin imminently after cutting out the last piece.

Right now, I am marking time while waiting for my teflon foot to arrive so I can get back to the leather jacket. It's going to be a bit of a pain to translate the very precise settings I had been using (on Kathryn Brenne's Bernina) to the very imprecise settings available on the Featherweight, but I am determined.

So in recent days, quite a lot of stuff around the edges of sewing happened here. This included:

- taking the lining out of the mink coat pictured in a recent post, reading Kathryn Brenne's article in Vogue Pattern Magazine several times, studying the construction of the coat, identifying Vogue 1083 as the perfect pattern for its transformation, thinking about the kind of fabric that would best complement it, rejecting every piece of fabric in my stash as unsuitable; shopping several websites without success, and trying to figure out if I'll have enough time to seriously look for fabric on my work-related trip to downtown Toronto later this week;

- making the lining pieces for my leather jacket (after all the adjustments it was easier to make the lining patterns from my altered pieces than to alter the included lining pieces);

- (finally) finishing the lining pattern for my Auckie Sanft jacket which was enthusiastically disassembled for this very purpose more than a year ago;

- cutting Jalie 2795 out of cushy blue-grey Power Stretch;

- washing and drying recently-acquired fabric; and

- putting fabric away (!) which is always a challenge chez The Sewing Lawyer due to an overabundance of fabric and an underabundance of storage locations.

Today I feel like more, maybe to include tracing Jalie 3024, which I think I'll shorten for now to another top suitable for exercise wear.

Wednesday, November 10, 2010

Invisible zipper pockets - an illustrated guide

One of the features of the Material Things Fearless Jacket is its in-seam zippered pockets. I figured the pattern is called "fearless" because you'd have to be to sew such a thing and expect it to look any good. I've put in my share of invisible zips over the years but tend to approach the task with a bit of a quaver in my voice, if you know what I mean. I learned how to do it back when the world was young and zippers came in packages with instructions. They said to sew the zipper in first and sew the seam closed afterwards, and you used one of those special blue plastic feet that fit on any kind of sewing machine. It's hard to manoeuvre your zipper foot close enough to the end of the zipper to make a really neat transition between zipper and seam. Sometimes you had to fudge a few hand stitches at the seam below the zipper opening. More often, you had to rip and re-sew. Neither would be a good idea in leather.

By contrast, Kathryn Brenne's method worked perfectly, the first time (a practice zipper) and the second and third times too (the real thing)! Here's how:

First, prepare your seam. Interface the pocket opening if it isn't already. In my jacket, the centre front panel is fully interfaced but not the side panel. I cut a strip of fusible and applied it as shown to the left. Mark the pocket opening. Then sew the seam above and below it. Press the seam open, including the seam allowances beside the pocket opening.

It turns out that things go a lot better when you have the right tricks up your sleeve. The trick, in this case, is Wonder Tape. Stick this stuff on the zipper tape, both sides, as shown to the right.

Next, peel off the Wonder Tape paper backing on one side. Position the zipper so the top stop is a little bit above the end of the stitching at the top of the pocket opening (above). The bottom stop should be a bigger bit below the end of the stitching at the bottom of the opening (right). Stick the zipper down on the seam allowance so that the coil is just along the pressed-open seam allowance on that side.

Sew that side of the zipper down using your choice of special foot. At left is the Bernina invisible zipper foot. The first side is easy, I tell you. The second is much harder because you have to somehow get the zipper coil in the opposite groove while the first side of the zipper is snugged right up against it. When I complained about this, Kathryn said "It'll be fine. That part of the stitching is in the seam allowance and you will never see it." She said exactly the same thing when I complained that it was hard to sew right to the bottom of the zipper on the second side.

And just look at the mess I made of it! Oh no!

Once both sides are sewn, you have to fish the zipper pull out of the little well you've sewn it into below the pocket opening so that it's accessible in the pocket opening.

Look! Kathryn was right! No sign of the ugly mess behind.

It'll be fine...

By contrast, Kathryn Brenne's method worked perfectly, the first time (a practice zipper) and the second and third times too (the real thing)! Here's how:

First, prepare your seam. Interface the pocket opening if it isn't already. In my jacket, the centre front panel is fully interfaced but not the side panel. I cut a strip of fusible and applied it as shown to the left. Mark the pocket opening. Then sew the seam above and below it. Press the seam open, including the seam allowances beside the pocket opening.

It turns out that things go a lot better when you have the right tricks up your sleeve. The trick, in this case, is Wonder Tape. Stick this stuff on the zipper tape, both sides, as shown to the right.

Next, peel off the Wonder Tape paper backing on one side. Position the zipper so the top stop is a little bit above the end of the stitching at the top of the pocket opening (above). The bottom stop should be a bigger bit below the end of the stitching at the bottom of the opening (right). Stick the zipper down on the seam allowance so that the coil is just along the pressed-open seam allowance on that side.

Sew that side of the zipper down using your choice of special foot. At left is the Bernina invisible zipper foot. The first side is easy, I tell you. The second is much harder because you have to somehow get the zipper coil in the opposite groove while the first side of the zipper is snugged right up against it. When I complained about this, Kathryn said "It'll be fine. That part of the stitching is in the seam allowance and you will never see it." She said exactly the same thing when I complained that it was hard to sew right to the bottom of the zipper on the second side.

And just look at the mess I made of it! Oh no!

Once both sides are sewn, you have to fish the zipper pull out of the little well you've sewn it into below the pocket opening so that it's accessible in the pocket opening.

Look! Kathryn was right! No sign of the ugly mess behind.

It'll be fine...

Tuesday, November 9, 2010

Leather Workshop - "It'll be fine"

This phrase was oft-repeated during the four days I spent working under Kathryn Brenne's supervision at her fantastic and well-equipped sewing studio in North Bay Ontario last week. Kathryn has endless patience and seems unfazed by any mistake or imperfection her students turn out (and there were some). And you know what? I think she's right - my leather jacket (which I shall finish once my teflon foot arrives from Mr. eBay) will be fine.

I did in the end go with the Material Things Fearless Jacket pattern. Kathryn mostly approved of the fitting changes I had made but on her recommendation I trimmed up the pieces even more. The first day of the class was mostly taken up with finalizing the pattern changes, and then making brown paper pattern pieces (doubles so there's a right and a left of everything for single layout on the skins). I had cut out some of it by the end of that day.

The second day was occupied with cutting out all the jacket pieces and interfacing, and fusing the interfacing where it needed to be fused. I had assembled the backs by the end of that day.

On day three I felt brave enough to tackle the invisible zipper pockets and assemble the jacket fronts. Day four involved sewing the sleeves and setting one of them in, inserting the front separating zipper, and almost completing the facings.

It doesn't seem like I did a lot each day, when I write it out like that, but believe me these were full days of sewing and associated learning (9AM to 5:30PM, with breaks for delicious homemade snacks and lunch). Of course if I had known what I was doing, I would have been more efficient...

Anyway, here are some photos of the sewing studio. It's on two levels.

Upstairs are the latest Berninas. Kathryn invited us to choose any one of them - I tried out the 640.

She also has two steam generator irons and a full kit of tools for every table.

Downstairs are the cutting tables, including one that was big enough for me to lay out five lamb skins at once. Here, Kathryn is examining another student's skins and talking about leather quality.

Kathryn is extremely generous with her knowledge and brought out numerous things for us to ogle and examine, including the fannnnnntastic sheared mink lined coat which is featured in the latest issue of Vogue Pattern magazine!

I was so inspired that when I spied an XL sized mink coat in good condition at the Value Village that night, I snapped it up.

That's it for now - stay tuned for pictures of my jacket in progress.

I did in the end go with the Material Things Fearless Jacket pattern. Kathryn mostly approved of the fitting changes I had made but on her recommendation I trimmed up the pieces even more. The first day of the class was mostly taken up with finalizing the pattern changes, and then making brown paper pattern pieces (doubles so there's a right and a left of everything for single layout on the skins). I had cut out some of it by the end of that day.

The second day was occupied with cutting out all the jacket pieces and interfacing, and fusing the interfacing where it needed to be fused. I had assembled the backs by the end of that day.

On day three I felt brave enough to tackle the invisible zipper pockets and assemble the jacket fronts. Day four involved sewing the sleeves and setting one of them in, inserting the front separating zipper, and almost completing the facings.

It doesn't seem like I did a lot each day, when I write it out like that, but believe me these were full days of sewing and associated learning (9AM to 5:30PM, with breaks for delicious homemade snacks and lunch). Of course if I had known what I was doing, I would have been more efficient...

Anyway, here are some photos of the sewing studio. It's on two levels.

Upstairs are the latest Berninas. Kathryn invited us to choose any one of them - I tried out the 640.

She also has two steam generator irons and a full kit of tools for every table.

Downstairs are the cutting tables, including one that was big enough for me to lay out five lamb skins at once. Here, Kathryn is examining another student's skins and talking about leather quality.

Kathryn is extremely generous with her knowledge and brought out numerous things for us to ogle and examine, including the fannnnnntastic sheared mink lined coat which is featured in the latest issue of Vogue Pattern magazine!

I was so inspired that when I spied an XL sized mink coat in good condition at the Value Village that night, I snapped it up.

That's it for now - stay tuned for pictures of my jacket in progress.

Sunday, October 31, 2010

Happy Hallowe'en!

I made a costume for my son when he was about 4 and obsessed with everything to do with dinosaurs. I had a book called Sew a Dinosaur - 21 playful prehistoric beasts to follow you home, which included a pattern for a kid-sized Triceratops costume.

The problem is, my son REALLY wanted to be a Tyrannosaurus Rex. They look nothing whatsoever like Triceratops.

Somehow or other, I did it.

Details: The head pieces were cut from cheap alligator-print knit over 1" foam backed with lining (bloody red for the inside of the head). The teeth and claws were more of the foam. I had to bone the head to keep the jaws out front, and to prevent the top one collapsing. Even so it wasn't the easiest costume for him to see out of.

The body is made without the foam. The tail was a cone of the alligator print sewn over foam. The base of the tail is circular, sewn to the back of the shirt. To keep the tail from dragging, I attached an elastic belt to the SAs on the inside, and it fit snugly around my son's hips. The tail stayed straight out and wiggled as he walked.

It was extremely cute, if I say so myself, and it was worn many times by many kids.

The problem is, my son REALLY wanted to be a Tyrannosaurus Rex. They look nothing whatsoever like Triceratops.

Somehow or other, I did it.

Details: The head pieces were cut from cheap alligator-print knit over 1" foam backed with lining (bloody red for the inside of the head). The teeth and claws were more of the foam. I had to bone the head to keep the jaws out front, and to prevent the top one collapsing. Even so it wasn't the easiest costume for him to see out of.

The body is made without the foam. The tail was a cone of the alligator print sewn over foam. The base of the tail is circular, sewn to the back of the shirt. To keep the tail from dragging, I attached an elastic belt to the SAs on the inside, and it fit snugly around my son's hips. The tail stayed straight out and wiggled as he walked.

It was extremely cute, if I say so myself, and it was worn many times by many kids.

Saturday, October 30, 2010

I made the same mistake ...

as Cidell. All together now: AAAAAARGH!

I made Kwik Sew 1680 (now oop).

I didn't forget to check the stretch of the fabric against the little "stretch to here" diagram on the pattern envelope. It passed in both directions.

I read Cidell's post and thought ... hmmm better check this so tried it on without elastic. Seemed OK.

In the end (oooooh bad pun!!), it was too short.

My fix (no I don't think I'll be modelling it here). Let's just call it a design feature.

This fabric is a swimsuit polyester made for Speedo but I won't wear this in the pool. (The Sewing Lawyer feels it's her obligation to keep her personal trainer awed by her vast wardrobe of exercise togs.) Inside is a shelf-bra made from the same super stretchy stuff (acquired in Montreal on PR weekend) that was used to line several sports bras, one of which can be seen here.

The fabric came from the Fabric Flea Market (you can find anything there, it seems). Here's a tour through my FFM acquisitions.

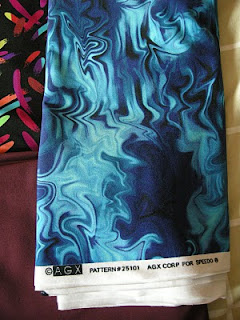

First, proof that this fabric really is Speedo, to the left. $5 per metre.

First, proof that this fabric really is Speedo, to the left. $5 per metre.

Right, some regular nylon/lycra. Same price (not as nice though).

To the left is a soft shell fabric (I think probably Polartec). It's a deeper colour than shown (at least on my monitor). I have enough for a jacket. Hello Jalie 2795!

This is a prize! It's silk from Thailand, 3.5 metres for all of $25. I thought it was an allover print (as below) but when I opened it up, turns out that half of it is a coordinating border print. Need I add that it's entirely hand-painted? Clearly it's intended for a specific type of use but I'm not sure exactly what. Any ideas?

To the right is a lovely knit print. I did a burn test which showed it is 100% natural, and washed/dried it in the machines without any change at all. It is definitely not rayon. It seems too fine to be cotton. I dunno. It's pretty. I seem to remember paying $15 for the piece (3m).

This one to the left isn't fairly represented because it's a really lovely deep purple rather than grey, in real life. 100% wool, lightweight and soft, $20 for the piece (another 3m). A dress?

I could also join the white shirt sewing brigade with these two. Pure cotton to the left (voile with more opaque woven-in floral pattern); lustrous cotton/silk to the right, also with woven-in pattern. $30 for the 2 pieces.

I could also join the white shirt sewing brigade with these two. Pure cotton to the left (voile with more opaque woven-in floral pattern); lustrous cotton/silk to the right, also with woven-in pattern. $30 for the 2 pieces.

Gotta get sewing....

I made Kwik Sew 1680 (now oop).

I didn't forget to check the stretch of the fabric against the little "stretch to here" diagram on the pattern envelope. It passed in both directions.

I read Cidell's post and thought ... hmmm better check this so tried it on without elastic. Seemed OK.

In the end (oooooh bad pun!!), it was too short.

My fix (no I don't think I'll be modelling it here). Let's just call it a design feature.

This fabric is a swimsuit polyester made for Speedo but I won't wear this in the pool. (The Sewing Lawyer feels it's her obligation to keep her personal trainer awed by her vast wardrobe of exercise togs.) Inside is a shelf-bra made from the same super stretchy stuff (acquired in Montreal on PR weekend) that was used to line several sports bras, one of which can be seen here.

The fabric came from the Fabric Flea Market (you can find anything there, it seems). Here's a tour through my FFM acquisitions.

First, proof that this fabric really is Speedo, to the left. $5 per metre.

First, proof that this fabric really is Speedo, to the left. $5 per metre.Right, some regular nylon/lycra. Same price (not as nice though).

To the left is a soft shell fabric (I think probably Polartec). It's a deeper colour than shown (at least on my monitor). I have enough for a jacket. Hello Jalie 2795!

This is a prize! It's silk from Thailand, 3.5 metres for all of $25. I thought it was an allover print (as below) but when I opened it up, turns out that half of it is a coordinating border print. Need I add that it's entirely hand-painted? Clearly it's intended for a specific type of use but I'm not sure exactly what. Any ideas?

To the right is a lovely knit print. I did a burn test which showed it is 100% natural, and washed/dried it in the machines without any change at all. It is definitely not rayon. It seems too fine to be cotton. I dunno. It's pretty. I seem to remember paying $15 for the piece (3m).

This one to the left isn't fairly represented because it's a really lovely deep purple rather than grey, in real life. 100% wool, lightweight and soft, $20 for the piece (another 3m). A dress?

I could also join the white shirt sewing brigade with these two. Pure cotton to the left (voile with more opaque woven-in floral pattern); lustrous cotton/silk to the right, also with woven-in pattern. $30 for the 2 pieces.

I could also join the white shirt sewing brigade with these two. Pure cotton to the left (voile with more opaque woven-in floral pattern); lustrous cotton/silk to the right, also with woven-in pattern. $30 for the 2 pieces. Gotta get sewing....

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)